History of Early Decision

With the specter of early decision bearing down on applicants this admissions season, some of you might be wondering how college admissions became so complicated. How did we come to have early decision, early decision II, early decision 0, early action, single choice early action, restrictive early action, deferrals, waitlists, ahhh!!

The Post-War Origins: When College Got Competitive

Believe it or not, Early Decision wasn't always part of the college admissions landscape. The system first emerged in the 1950s, and like many things that make our lives more complicated, it started with good intentions.

Picture this: It's the years following World War II, and American higher education is experiencing an unprecedented boom. Thanks to the GI Bill and a growing middle class, college enrollments are surging. Elite schools that once accepted virtually all qualified applicants suddenly find themselves drowning in applications. For the first time, they actually have to turn people away.

This created a two-way anxiety spiral. Students worried: "Will my top-choice college accept me?" Colleges worried: "Will the students we admit actually show up?" Remember, this was long before the Common App era of applying to 20+ schools. But even then, colleges were starting to lose their top admits to competing institutions, and they didn't like the uncertainty.

Enter Early Decision: the original solution to reduce everyone's anxiety. The deal was simple—students who were absolutely certain about their first-choice school could apply early and get an answer by December. In exchange for that early acceptance, they pledged to attend, giving colleges more control over their yield rates (the percentage of admitted students who actually enroll). Everyone wins, right? Well, sort of.

The Early Days and Evolution

By the 1960s and 70s, early admissions became a serious recruitment tool. Some colleges were filling most of their freshman class through early admissions. The Ivy League, characteristically, did their own thing for a while—they sent certain applicants an "early letter" with grades of A, B, or C. An 'A' meant you were basically in, which must have been nice (and considerably less stressful than refreshing your portal at midnight).

The modern Early Decision programs as we know them really took off in the 1980s and 1990s, right as college admissions was becoming a national sport. More schools adopted ED, more students started applying to multiple colleges, and the arms race was officially on.

Then in 1976, something interesting happened. A group of elite schools—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, MIT, and others—introduced a gentler alternative: Early Action. Same early timeline, same early decision, but non-binding. Students could apply early, get that coveted early answer, but weren't locked in. They could still compare financial aid packages and make their final choice in the spring. Revolutionary!

The Great Early Admission Debate

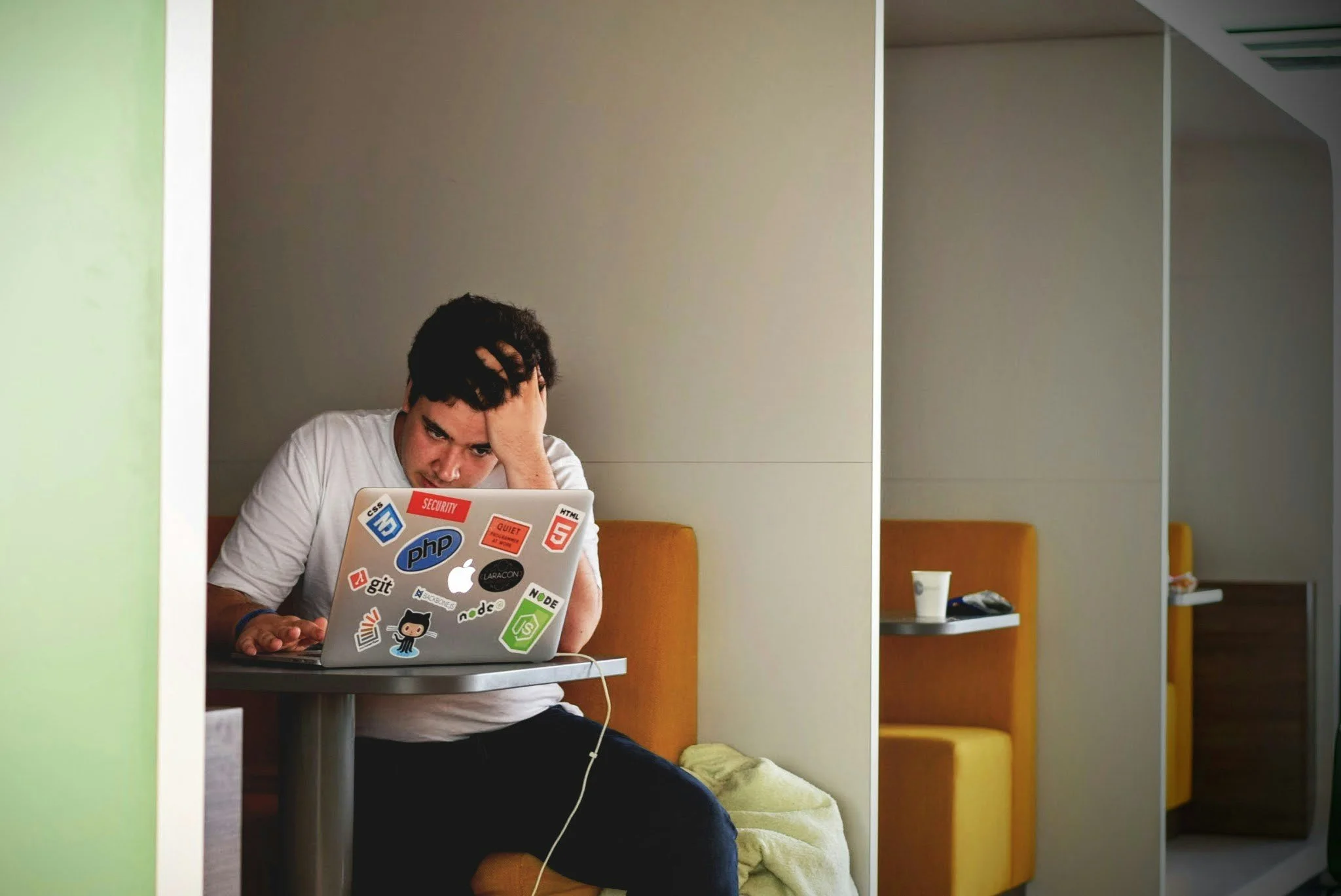

Here's where things get messy. From the beginning, Early Decision had critics who pointed out the obvious: this system really favors students from well-off, well-advised families. Low-income students often can't commit to a binding decision without comparing financial aid packages. First-generation students might not even know Early Decision exists, or might not have their application materials ready by November of senior year.

The criticism reached a fever pitch in the mid-2000s. In 2006, Harvard and Princeton made headlines by very publicly dropping their early admission programs entirely, declaring them unfair to less-privileged applicants. The University of Virginia followed suit in 2007, citing concerns that their ED pool "lacked racial and socioeconomic diversity."

It was a bold moral stance. It lasted about five minutes.

Within a few years, most of these schools quietly brought early admissions back. Why? Because while they were taking the high road, their competitor schools were still offering early plans and scooping up all the top students. Harvard and Princeton reinstated their early programs by 2011—though notably, they chose Single-Choice Early Action instead of binding ED, trying to split the difference between competitive advantage and fairness concerns.

How We Got to This Alphabet Soup

So how did we end up with ED, ED II, EA, REA, SCEA, and whatever other acronyms will be invented by next year?

It's actually a fascinating case study in strategic evolution. Each policy tweak is colleges trying to solve a different problem:

Early Decision gives colleges maximum yield control—if you're admitted, you're definitely coming

Early Action attracts more applications because it's lower risk for students

Restrictive/Single-Choice Early Action (like Harvard, Yale, Stanford use) attempts to get the "you're my first choice" signal without actually binding students

Early Decision II emerged as a second chance for students who missed the ED I deadline or got deferred elsewhere

Various restrictions (like Georgetown's "you can apply EA here but not ED anywhere else") are attempts to prevent students from gaming multiple systems at once

Each policy is a school trying to optimize its own enrollment management while staying competitive with peer institutions. Some schools switched from EA to ED (looking at you, Boston College) because too many EA admits were choosing other colleges. Others offer both ED and EA because why not hedge your bets?

If you or a loved one is feeling pressured by the impending early decision and early action deadlines, schedule a consultation with an admissions expert today so we can relieve as much of that pressure as possible and provide you crystal clear guidance on what you can be doing right now to get into your dream school.