Is Being Class President a Good Extracurricular?

Ask any parent who went to high school in the 80s or 90s, and they'll tell you the same thing: class president was the extracurricular. It was the gold standard. In every teen movie from that era, think Ferris Bueller, Election, Mean Girls, the class president was the one going places. They were destined for greatness, respected by peers and teachers alike, and come senior year, they were holding an acceptance letter from an elite university. The narrative was clear: run the school, get into the best college, become a senator. It was almost a formula.

That formula no longer works. And if your student is banking on class president to anchor their college application, you need to read this carefully.

The old logic wasn't wrong for its time. Decades ago, the college admissions landscape was far more contained. If you wanted to impress Harvard, you largely worked with what your high school offered: AP classes, sports teams, the school play, and student government. The ceiling was your school, and the class president sat squarely at that ceiling.

More importantly, students back then were genuinely tied to their school communities in a way that made class president meaningful. There weren't summer research programs at Johns Hopkins or MIT. There weren't online courses, national debate circuits, congressional internships, or independent research journals for high schoolers. If you wanted to lead, student government was one of the few real stages available. And in that context, being elected class president did say something, it showed leadership, social capital, and the ability to organize people toward a goal.

Admissions officers of that era understood the role within that limited ecosystem and rewarded it accordingly.

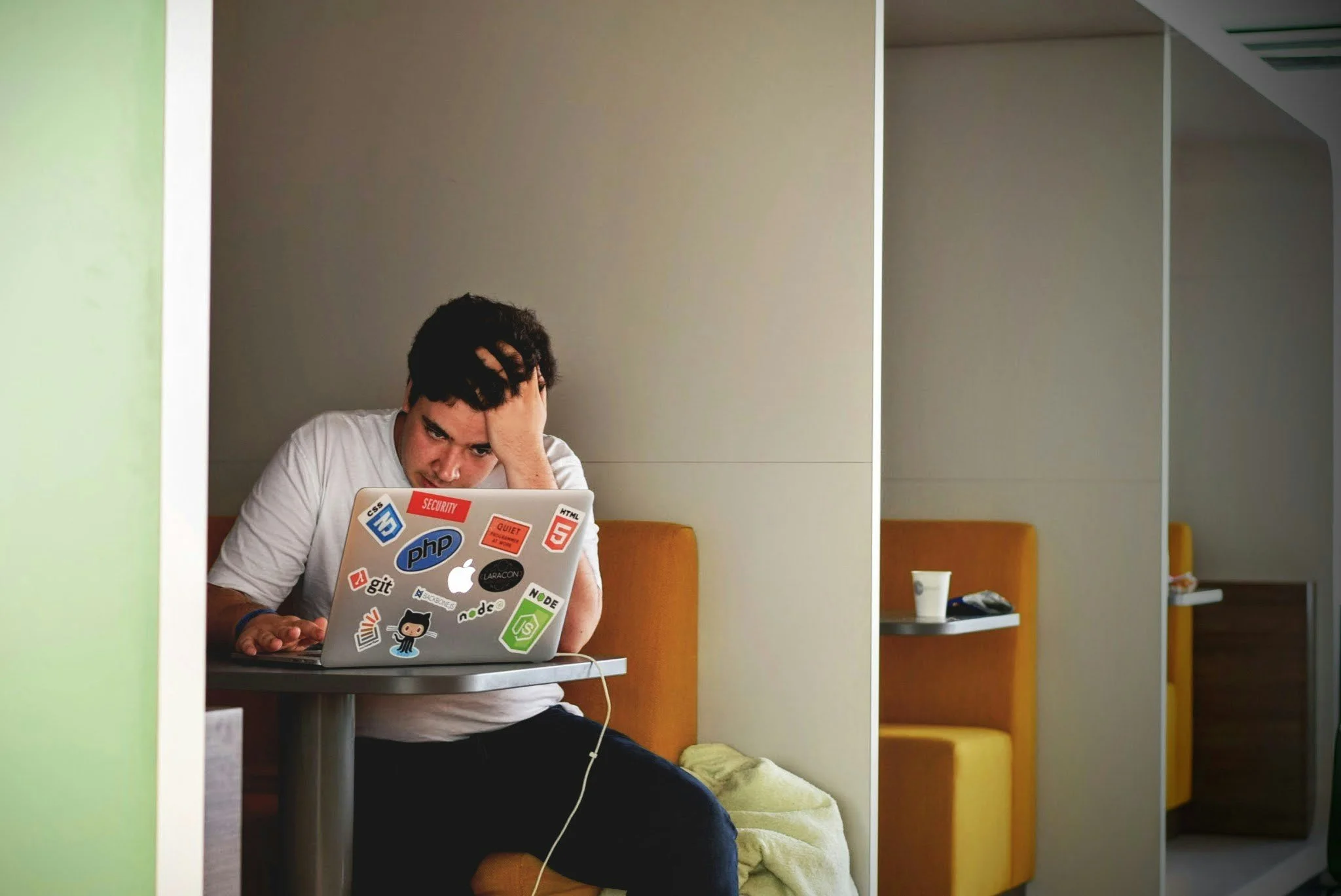

The world student lives in today looks nothing like that. Today, a motivated high schooler can co-author a research paper with a university professor, launch a nonprofit that helps get local legislation passed, build software used by thousands of users, or compete at the national level in science olympiad, math olympiad, or debate. They can take real college courses for credit, intern at biotech startups, and publish essays in nationally recognized journals, all before senior year.

This expansion didn't just add options. It fundamentally changed the bar. Admissions officers at MIT, Stanford, and the Ivies have spent the last two decades recalibrating what "leadership" and "impact" actually mean. The result is a shift toward what admissions insiders call spike profiles, students with deep, demonstrable, real-world impact in a specific area, rather than the old-school well-rounded profile that student government once anchored.

Class president hasn't changed. The world around it has.

Here's the core issue: elite admissions today is obsessed with one question. What did you actually change? Not in a hypothetical, student-government-resolution kind of way, but concretely, measurably, in the real world.

And this is where class president runs into trouble. What does a class president actually do? They plan pep rallies, manage a budget for homecoming, speak at assemblies, and advocate to administrators for things like later lunch periods or new vending machines. These aren't trivial, they require real social skills and organizational ability, but they don't move the needle on the kinds of outcomes elite colleges are looking for.

Compare that to a student who spent the same time working with a city council member to pass an ordinance, organizing a voter registration drive that enrolled thousands of residents, or founding an advocacy organization with documented legislative wins. For students interested in politics, law, or public policy, admissions officers at top schools have seen what genuine civic engagement looks like. Playing school president next to that is a difficult sell.

The irony is that the skills class president is supposed to demonstrate, leadership, persuasion, civic responsibility, are now much more convincingly demonstrated through actual political engagement. Why simulate governance when you can participate in the real thing?

You do still see class presidents at Harvard and Yale, that's true. But when you look closely, something interesting emerges: it's almost never because they were class president.

In most cases, these students have a separate, genuinely compelling spike. Their research, their athletic achievement, their artistic portfolio, or their real-world advocacy is carrying the application. Class president is background noise on the activity list. In other cases, and this is worth saying plainly, legacy status and donor family connections create a different admissions pathway entirely, one where social popularity at a well-resourced school isn't penalized the way it might be for other applicants. Those students can afford to spend time becoming popular enough to win a school election because they don’t need the deeper impact activities that others need.

To be fair, class president isn't the worst use of time on the extracurricular spectrum. It still demonstrates real social skills and requires you to manage people and politics in a low-stakes environment. As a secondary activity, something that coexists with a stronger primary spike, it's unlikely to hurt you.

It lands, in our view, a step above something like DECA, which has become so universally common that it reads as a checkbox rather than a commitment. Class president at least requires a school community to vouch for you through an election. But that's a fairly modest distinction, and it doesn't change the fundamental calculus: in 2025, class president is a supporting character at best, and spending significant time and social energy chasing the role, at the expense of developing real-world impact, is a strategic mistake.

If you need help trimming the fat of your current extracurriculars so you can use your time better to distinguish yourself, need help selecting which activities to participate in, or have any other questions related to the college admissions process, schedule a free consultation with an admissions expert today.