How Has The College Admissions Process Changed?

If you applied to college in the 1980s, '90s, or early 2000s, you probably remember the basics: get good grades, take the SAT, join a few clubs, write one essay, mail your application, and wait. For the most selective schools, competition was real, but the process felt finite, legible, and bounded by what your high school offered.

What your child is facing today is recognizably related to that process. But it has been transformed in ways that aren't always obvious, and misunderstanding those changes is one of the most common ways well-meaning parents accidentally give their kids outdated advice.

Here's what actually shifted, and what it means for families navigating admissions right now.

The Application Volume Explosion

The single biggest structural change is one most parents don't fully appreciate: the sheer scale of competition has increased dramatically, and the friction of applying has nearly disappeared.

When the Common App launched its online platform in 1998, it became dramatically easier to apply to many schools at once, fewer paper forms, easier submission, streamlined fee waivers. Research suggests that joining the Common App is associated with roughly a 10% increase in applications in the first year at member schools, and around 25% more after a decade. More recently, platforms like the Coalition App expanded options further.

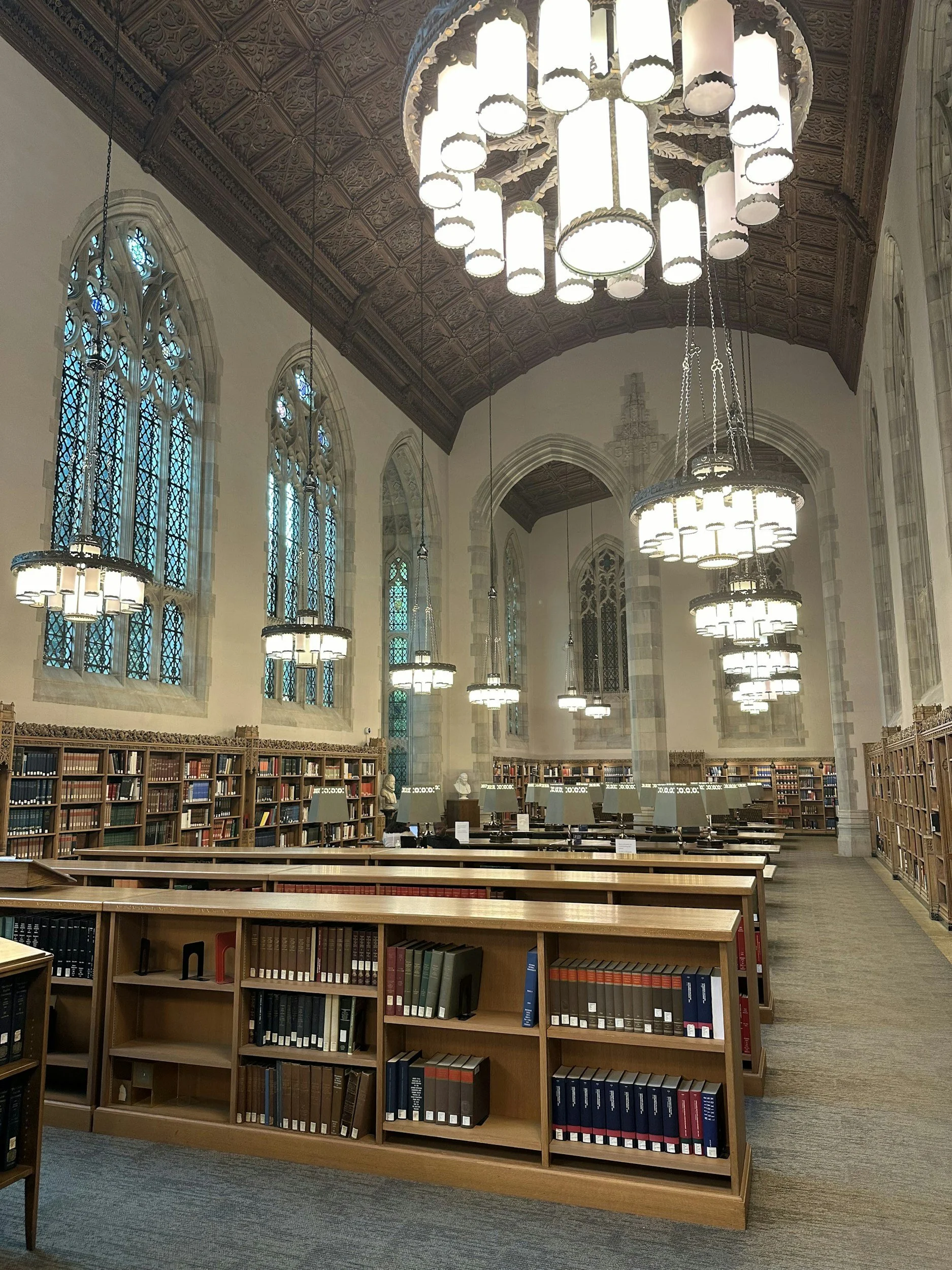

The practical result: elite schools now receive application pools that dwarf what existed when you applied. Harvard, MIT, and Stanford regularly turn away the majority of valedictorians and perfect scorers who apply. This isn't because standards got harder, it's because the pool got bigger and easier to enter.

What this means for your family: Your child isn't competing against a local or regional applicant pool anymore. They're competing against the best-prepared students from across the country and internationally, all of whom can apply with a few clicks.

Academic Rigor Is No Longer Just "Your Hardest Classes"

When most of today's parents applied, academic rigor meant taking the hardest courses your high school offered. usually honors classes and whatever AP sections were available. AP participation in 1980–81 amounted to roughly 178,000 exams taken nationally. That number hit 5.7 million in 2023–24.

That's not just growth, it's a categorical shift. Advanced coursework has gone from being a differentiator to being a baseline expectation for competitive applicants. And it doesn't stop at the high school building anymore.

Dual enrollment, taking actual college courses while still in high school, was taken advantage of by roughly 813,000 students in 2002–03. By 2022–23, newer estimates put that number near 2.5 million. By 2017–18, 82% of public high schools offered some form of dual or concurrent enrollment. Online community college courses, quarter-system classes, and distance learning have all become standard tools in a competitive applicant's toolkit.

Princeton, MIT, and Stanford all explicitly reference college-level coursework taken during high school as part of their academic preparation guidance. It is no longer exotic, it is normalized.

One important nuance: Admissions value and transfer credit are separate questions. MIT, for example, acknowledges that "college classes taken during high school" can strengthen an application, while also noting that most online classes and dual enrollment courses won't qualify for transfer credit once enrolled. The goal is demonstrating readiness, not skipping coursework.

What this means for your family: "Take the hardest classes available" is still the right advice, but what's "available" has expanded enormously. Your child's transcript will be evaluated in context of what their school offers, but a competitive applicant needs to understand and potentially pursue options beyond the traditional high school schedule.

Extracurriculars: Quality Beat Quantity — And It's Official Policy Now

Here's where a lot of parents pass down genuinely harmful advice without realizing it. The old instinct was: join as many clubs as possible, be a well-rounded student, fill every line on the application.

That was never really how elite admissions worked, but today, Harvard and MIT are explicitly telling applicants the opposite.

Harvard's admissions guidance states directly: "We are much more interested in the quality of students' activities than their quantity." MIT is equally blunt: "We don't expect applicants to do a million things. Choose quality over quantity."

This isn't empty rhetoric. The shift reflects a real change in how large applicant pools work: when every competitive applicant has a crowded resume of clubs and activities, quantity stops being a differentiator. What stands out is depth, sustained commitment to something, real leadership, measurable impact, genuine skill development. Admissions officers often call this a "spike": a student who has gone deeply into something and has the results to show for it.

It's also worth knowing that modern research into extracurricular reporting at scale, drawn from millions of Common App submissions, has documented significant disparities in activity portfolios by race and socioeconomic status. Elite schools are increasingly attentive to context: a student who held a part-time job or cared for younger siblings may have had fewer formal activities, and that's something applications now explicitly invite students to explain.

What this means for your family: Encourage your child to go deep on one or two things they genuinely care about, not wide across a dozen that look good on paper. Family responsibilities and paid work are legitimate activities, elite schools say so directly. Outcomes and impact matter more than participation.

Essays: You Now Write a Portfolio, Not a Statement

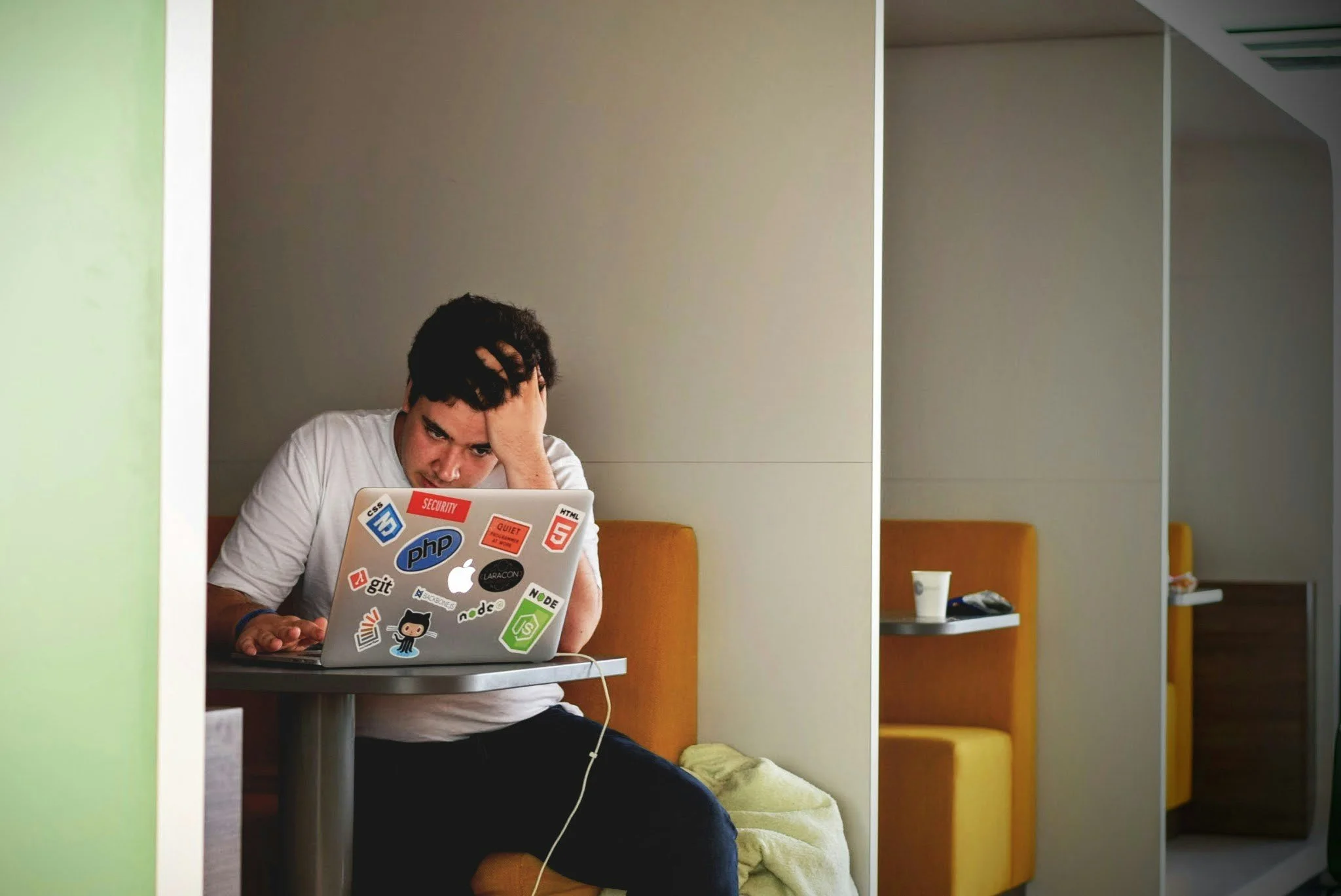

When most parents applied, the essay requirement was simple: one personal statement, sometimes one supplemental. Today's applicants to elite schools complete what is effectively a writing portfolio.

The Common App essay (up to 650 words) is just the entry point. On top of that, competitive schools stack their own requirements:

MIT uses several short responses and explicitly tells applicants "this is not a writing test, be honest, be authentic"

Stanford requires the Common App essay plus its own "Stanford Questions," including several short prompts and 100–250 word essays

Yale adds multiple short answers including prompts as brief as 200 characters

Princeton requires applicants to submit a graded academic paper from high school — an explicit evaluation of writing in an academic setting

Harvard adds five required short-answer questions (150 words each) on top of the Common App essay

The purpose of this portfolio approach is deliberate. Schools aren't just asking "can you write?" They're asking: How do you think? What do you value? How do you engage with ideas and with other people? Does your voice fit our community?

For 2025–26, the Common App has also tightened its "Additional information" section from 650 words down to 300, and redesigned its context and circumstances prompts to better capture challenges like technology access, family disruption, health issues, and housing insecurity, all in structured, concise formats.

What this means for your family: Your child needs a writing strategy across all their prompts, not just a single polished essay. Each piece should add new information, not repeat what's already on the résumé or in the activities section. Planning the full portfolio early is essential.

Standardized Testing: It's Complicated Again

For most of your era, standardized testing was simple: the SAT (or ACT) was required, everyone took it, and scores were a meaningful common denominator. Then COVID happened.

The pandemic triggered a wave of test-optional policies across elite schools that lasted several years. Many families, and students, assumed test-optional was the new permanent reality. It wasn't.

MIT announced a return to requiring the SAT/ACT, explicitly arguing that tests help assess readiness and can identify talented students across unequal educational environments. Harvard announced a similar return to required testing. Princeton has also signaled a phased return to test requirements.

Other schools remain test-optional, and policies continue to shift year to year.

What this means for your family: Test preparation is back on the table, but it's now school-specific and cycle-specific rather than universal. Families targeting elite schools should build a test plan early enough to preserve flexibility. Don't assume last year's policy will be this year's policy.

The Legal Landscape Changed Dramatically in 2023

This one has no parallel in your admissions experience. In June 2023, the Supreme Court's decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. UNC ended race-conscious admissions as elite universities had practiced it for decades.

Institutions can no longer use race as a categorical factor in admissions decisions. However, the majority opinion explicitly preserved the ability of applicants to discuss how race affected their personal experiences, provided that any benefit flows from the individual's specific traits and experiences, not from racial identity itself.

The practical result is that essays have become even more consequential as a venue for conveying the full texture of an applicant's background and identity, within the new legal constraints that schools and applicants alike are still working to understand.

Separately, legacy and athletic admissions preferences are facing unprecedented scrutiny. Johns Hopkins has eliminated undergraduate legacy preferences entirely. California enacted a law banning legacy and donor preferences in private nonprofit college admissions, effective 2025. Research published in peer-reviewed economics journals and made public during the Harvard litigation has quantified just how large these advantages were, and that visibility has made them politically and legally vulnerable in ways they weren't a generation ago.

What this means for your family: The rules of the game are genuinely in flux. If you were counting on legacy status, don't. If your child's background, racial, socioeconomic, geographic, feels like an important part of who they are, working with an experienced counselor on how to convey that authentically and effectively within the current legal framework matters more than ever.

The Bottom Line for Parents

The college admissions process your child is navigating is built on the same foundations you remember: strong academics, meaningful activities, authentic writing, and a compelling case that they'll contribute to a campus community. That hasn't changed.

What has changed is the competitive environment, the range of tools and signals available, the legal framework, and the volume. The students who succeed at elite schools today are usually those who specialized early, went deep on something real, built a coherent narrative across their application, and tested into strong scores at schools that require them.

The parents who help most are those who update their mental model of what "good" looks like, not the well-rounded student of the 1980s, but the focused, authentic, outcome-oriented student of today.

If you're not sure where your child stands or how to help them position themselves effectively, that's exactly what we do at Cosmic. If you need help navigating this brave new world of college admissions, schedule a free consultation with a college admissions expert today.