Is Starting a Nonprofit a Good Extracurricular?

The short answer is yes, but most students get it catastrophically wrong.

Walk into any competitive high school in America and you'll find at least a handful of students who have "founded a nonprofit" somewhere on their resume. Admissions officers at MIT, Stanford, and the Ivies have seen thousands of them. And most of the time, they're not impressed.

That doesn't mean starting a nonprofit is a bad idea. Quite the opposite. Done right, it's one of the most powerful extracurriculars a student can have. The problem is that done wrong, it can actively hurt you.

Admissions officers are professionals. Their entire job is to read between the lines of an application and understand the real story behind what a student is presenting. When they see a nonprofit on a resume, their first instinct isn't admiration, it's scrutiny.

They're asking themselves: Did this student actually build something meaningful, or did they create a website, file some paperwork, and call themselves a founder?

When a nonprofit reads like a checkbox, something a student started because they heard it looks good, colleges see it immediately. The language is vague. The impact is unmeasurable. The timeline is suspiciously short, often coinciding with the student's junior year. Admissions officers don't just ignore these entries. They can penalize students for them, because it signals a willingness to game the system rather than actually contribute to the world.

The bar isn't "did you start a nonprofit." The bar is "did you build something real."

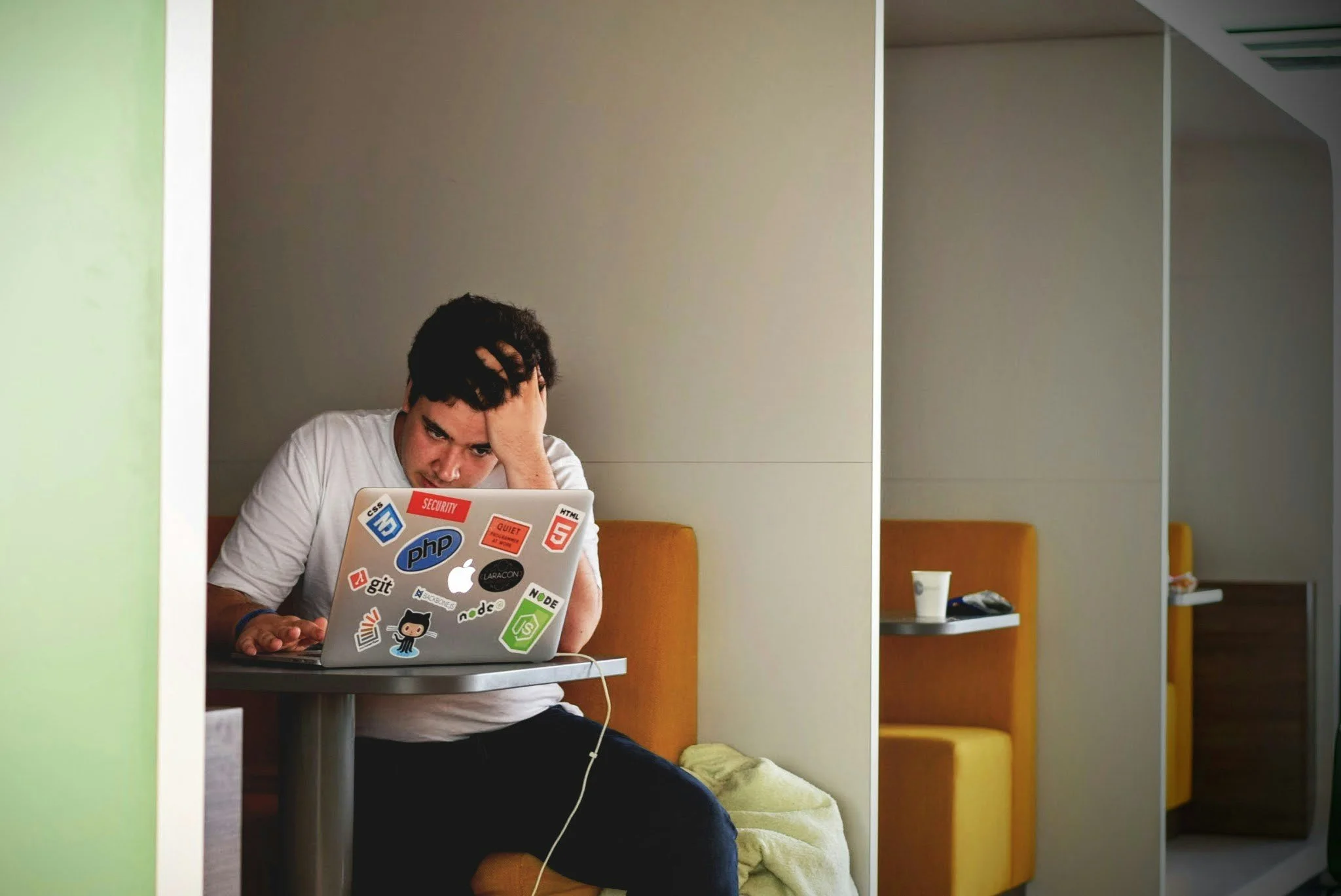

Here's the uncomfortable truth about starting a genuine nonprofit: it demands the kind of commitment most high schoolers aren't prepared to give.

To actually get a nonprofit off the ground, to build a functioning organization with measurable impact, a real donor base, community partners, and demonstrable results, you need to be investing 20 to 40 hours a week, for a full year, minimum. That's not an exaggeration. That's the reality of what it takes to turn an idea into an institution.

This isn't a weekend project. This isn't something you do while maintaining a full course load of AP classes, playing a varsity sport, and padding three other clubs onto your application. If you treat it that way, colleges will know. The impact numbers won't be there. The depth won't be there. The story won't hold up under questioning in an interview.

If you genuinely cannot commit at that level, a nonprofit is not the right move for you right now, and that's completely fine. There are plenty of other ways to demonstrate leadership and impact.

But if you can make that commitment? The opportunity is extraordinary, precisely because so few students actually do.

There's a second element of a successful nonprofit application that almost no one discusses: what happens to the organization after you leave for college.

Admissions officers are thinking about this. A nonprofit that is clearly built around one person, that will collapse the moment that person walks out the door, raises serious questions. Did this student build an organization, or did they build a personal brand project? Is this about impact, or is it about a line on a resume?

You need to answer this question before the admissions officer even has a chance to ask it.

That means one of two things. Either your nonprofit is structured to continue growing under new leadership, with trained successors, documented systems, and institutional relationships that don't depend on you personally, or you make a compelling case that you yourself will continue leading the organization through college, taking on a remote executive or advisory role while your organization's on-the-ground team carries day-to-day operations.

Both are legitimate. Both can be convincing. But you need to have a clear, credible answer. "I'll find someone to take over eventually" is not an answer.

The nonprofits that genuinely move admissions committees share one characteristic: they solve a problem that is real, specific, and verifiable.

The best place to start is your own community. Local problems have several advantages. You have direct access to the people affected. You can build relationships with local institutions, schools, government agencies, community organizations, that lend credibility to your work. And your results are tangible and demonstrable in ways that broad, abstract missions rarely are.

"Addressing global inequality" is not a problem. "Connecting low-income students in our school district with free SAT prep tutoring, resulting in a 120-point average score increase across 47 students" is a problem with a solution.

That said, if your nonprofit really takes off, and some do, the calculus changes. Students who build organizations that raise tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, develop replicable program models, or generate genuine media attention have earned the right to pursue larger problems. That kind of scale is rare, and it speaks for itself. But that scale has to be real. Manufactured press releases and inflated donor lists fool no one.

Starting a nonprofit is one of the highest-ceiling extracurriculars available to a high school student applying to elite universities. The ceiling is high because the floor is demanding, and most students aren't willing to meet it. That creates a genuine opportunity for those who are.

If you're willing to commit a year of serious, sustained efforts, to build something that solves a real problem, that can survive without you, and that produces results you can actually measure, then yes, a nonprofit can be an outstanding centerpiece of your college application.

If you're looking for something that looks like a nonprofit without the work of actually building one, admissions officers will see that. And that's worse than not having one at all.

If you need help trimming the fat of your current extracurriculars so you can use your time better to distinguish yourself, need help selecting which activities to participate in, or have any other questions related to the college admissions process, schedule a free consultation with an admissions expert today.