Do You Have to Play an Instrument in High School to Get Into College?

Let's cut through one of the most persistent myths in college admissions: No, you do not need to play a musical instrument to get into Harvard, MIT, Stanford, or any other highly selective university. Not one of the Ivy League schools requires it. Not one of the top 20 universities requires it for general undergraduate admission. This isn't a matter of interpretation or reading between the lines—it's simply not part of the admissions requirements.

And yet, the question keeps coming up. Parents worry their child is at a disadvantage without piano lessons. Students wonder if they should pick up violin junior year to round out their application. The anxiety is real, even if the requirement isn't.

So where does this myth come from, and what's the actual role of music in elite college admissions? More importantly, if you do play an instrument, how do you know whether it will actually help your application, or whether you're better off investing that time elsewhere?

Why the Myth Persists

The confusion is understandable. Walk through any Ivy League campus and you'll find exceptional musicians everywhere, symphony orchestras, chamber groups, jazz ensembles. Many admitted students do play instruments, and they play them well. But correlation isn't causation. These students weren't admitted because they play music; they were admitted because they demonstrated the kind of sustained commitment, discipline, and achievement that happens to show up in their musical pursuits among other areas of their lives.

The myth also gets reinforced by the existence of optional arts supplements at many top schools. Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Brown, Dartmouth, Cornell, Columbia, MIT, Stanford, Chicago, Caltech, Duke, Johns Hopkins, Notre Dame, and Washington University all provide pathways for students to submit recordings, portfolios, or other artistic materials. When students see these options, they sometimes conclude that they need to submit something to be competitive. But the word "optional" here is doing real work, most admitted students at these schools do not submit arts supplements at all.

Among the 23 universities that consistently rank in the top 20 of U.S. News National Universities rankings (including all eight Ivies), schools fall into three distinct categories when it comes to arts supplements:

Schools that welcome optional arts supplements (Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Brown, Dartmouth, Cornell, Columbia, MIT, Stanford, Chicago, Caltech, Duke, Johns Hopkins, Notre Dame, WashU): These institutions provide structured pathways, often through platforms like SlideRoom, for students to submit recordings or portfolios. But the language is consistent across all of them: supplements should document "extraordinary," "exceptional," or "significant" artistic achievement. These are not meant to be résumé-padding exercises. They're meant to provide context for students whose artistic development is genuinely at a level that standard application components can't adequately convey.

Schools that explicitly do not review unsolicited arts materials (Penn, Northwestern, Rice, Vanderbilt, UCLA, UC Berkeley, Carnegie Mellon, Michigan): These universities either limit portfolio review to specific major programs or state outright that they don't evaluate arts supplements for general admission. Northwestern is particularly direct about this: it does not accept unsolicited portfolios, recordings, or websites for review in undergraduate admissions. UC Berkeley states it is "unable to accept portfolios or other supplemental materials." When schools are this explicit, students should take them at their word.

Schools with program-specific requirements (Northwestern's Bienen School of Music, Rice's Shepherd School, Vanderbilt's Blair School, UCLA performing arts majors, CMU's School of Music, Michigan's SMTD): If you're applying to these dedicated music programs, auditions and prescreening are required and often serve as the primary admissions gate. But this is a completely different question than whether you need to play an instrument to get into Northwestern, Rice, Vanderbilt, UCLA, Carnegie Mellon, or Michigan as a biology or economics or computer science major. You don't.

What Matters

If you're considering whether music will strengthen your college application: the level at which you perform, and how that music connects to your broader intellectual and personal narrative.

For traditional classical instruments like piano and violin, where competition is particularly intense, casual participation simply doesn't register. If you're submitting a music supplement at a school that reviews them, admissions offices expect, and the research backs this up, that your playing should be competitive at the level where significant cash prizes are awarded at regional or national competitions. We're talking about students who have won or placed at competitions like MTNA, Chopin Foundation, Liszt International, or similar caliber events. We're talking about students with All-State or All-National honors, students who have performed as soloists with orchestras, students whose teachers are faculty at major conservatories.

This isn't meant to discourage you if you're a serious musician working toward that level. It's meant to give you a realistic benchmark. An admissions officer listening to your recording has likely heard submissions from students who study at pre-college programs at Juilliard, Curtis, or New England Conservatory. Your recording will be evaluated by music faculty members who understand what exceptional playing sounds like. The bar is genuinely high because these supplements are optional, schools only want you to submit if you're clearing that bar.

The Narrative Challenge: Beyond "Music Relaxes Me"

Even if you are performing at an elite competitive level, there's a second critical consideration: how does your music connect to the rest of your application narrative?

The weakest musical supplements, and the weakest music-focused essays, are the ones that treat music as a generic extracurricular that could belong to anyone. "Playing piano helps me find serenity." "Music is where I explore my creativity." "Orchestra taught me teamwork." These themes are written by thousands of applicants every year. They don't differentiate you, and they don't give admissions officers insight into who you are as a thinker or what you'll contribute to campus intellectual life.

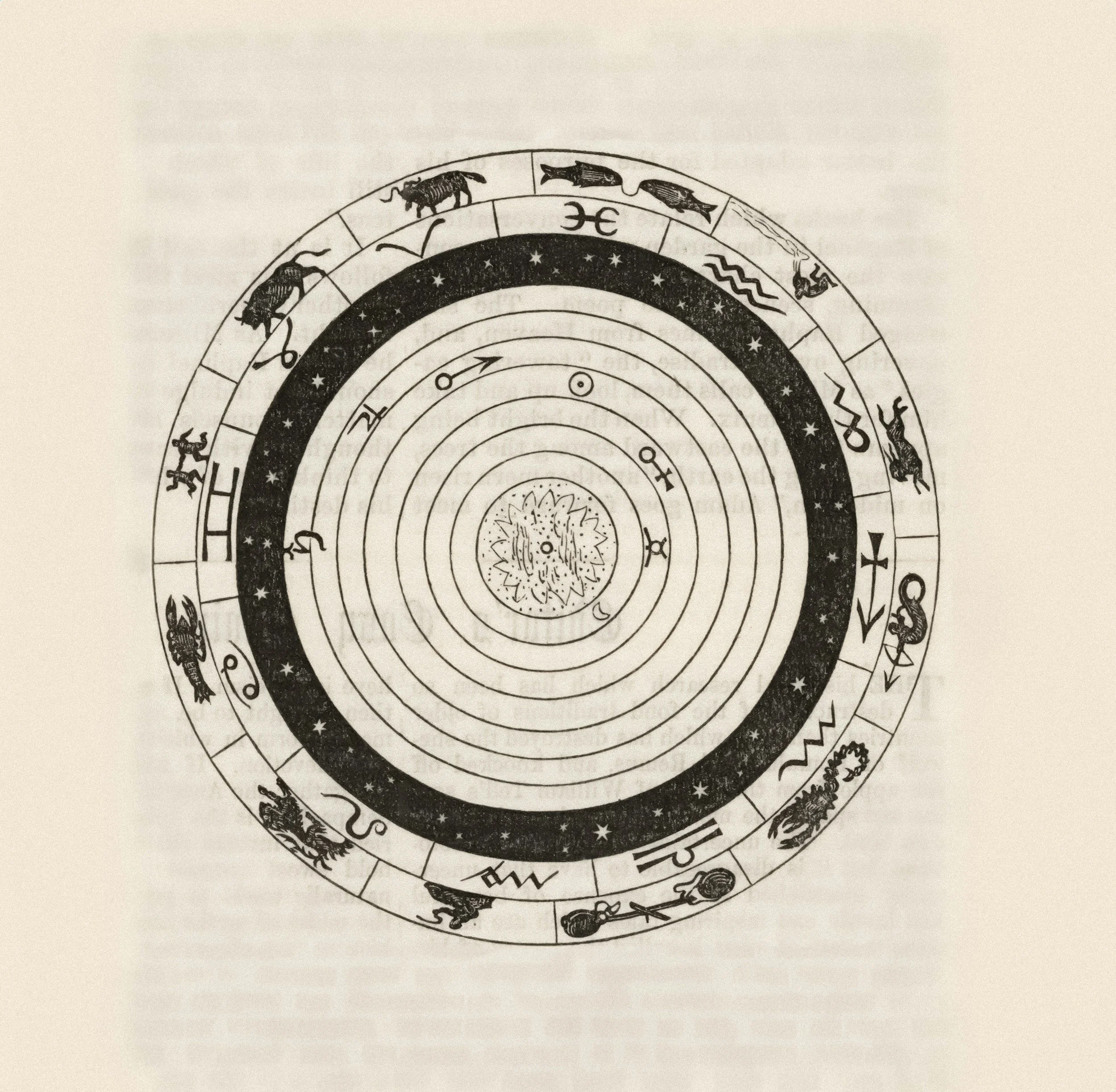

For students applying to schools that do review arts supplements, the music you submit should ideally align with your intended major or intellectual trajectory in some way that creates a distinctive narrative. Maybe you're a prospective neuroscience major whose understanding of music cognition and auditory processing has shaped your research interests. Maybe you're planning to study computer science and your work with algorithmic composition or music information retrieval represents a genuine synthesis of your technical and artistic pursuits. Maybe you're interested in mathematics and your engagement with tuning systems, harmonic ratios, or the mathematical structures underlying different musical traditions reflects how you think about abstract systems.

The key is that your artistic work should be part of a story about your intellectual development that only you could tell. It should reveal something specific about how you think, what you're curious about, how you've pursued that curiosity in unconventional ways. Generic narratives about stress relief and self-expression don't accomplish this.

This is particularly important for students considering music supplements at STEM-focused schools like MIT or Caltech. Yes, both schools accept creative portfolios and explicitly welcome submissions that show different facets of applicants (Caltech specifically mentions "playing an instrument" in its supplemental materials guidance). But the students whose music supplements strengthen their STEM applications are typically students who can articulate genuine intellectual connections between their artistic and technical work, not students who are presenting music as simply "something else I do."

Strategic Takeaways

Let's crystallize this into actionable guidance:

If you're already a serious musician: Continue if it's authentic to who you are and if you're performing at a genuinely elite level. Where optional arts supplements exist, consider submitting only if you're competitive at the level described above, and only if you can connect your musical development to your broader intellectual narrative in a way that's specific and compelling. Follow each school's submission guidelines exactly.

If you don't play an instrument: Don't start now for admissions purposes. Channel that time and energy into developing genuine distinction in areas that matter to you. Build something, discover something, contribute something that demonstrates sustained commitment and meaningful impact. This is what selective admissions is actually looking for.

If you need help trimming the fat of your current extracurriculars so you can use your time better to distinguish yourself, need help selecting which activities to participate in, or have any other questions related to the college admissions process, schedule a free consultation with an admissions expert today.