Do You Have to Play a Sport in High School to Get Into College?

One of the most persistent myths in college admissions is that you need to play a sport, any sport, to be competitive at top universities. We hear this constantly from anxious students and parents: "My daughter focuses on research and math competitions, but she's never played varsity sports. Is that going to hurt her at MIT?" Or: "My son quit soccer to focus on coding projects. Did we make a mistake?"

The short answer: No, you don't need to play sports to get into elite colleges, including the Ivy League.

But like most things in admissions, the real answer requires nuance. Let's break down what top universities actually say, what the data shows, and what this means for students who've never touched a lacrosse stick.

What Admissions Offices Actually Say About Sports

When you read through official admissions guidance from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, MIT, Stanford, and their peers, you find remarkable consistency: sports are never listed as a requirement.

Instead, these schools emphasize:

Pursue what you genuinely care about. Yale explicitly warns it's "fruitless to worry too much about any one" component and advises applicants to "pursue what you love."

Extracurriculars are about understanding you as a person. Princeton seeks students who will contribute "intellectually and socially, both inside and outside the classroom," defining "activities" broadly to include jobs, responsibilities, and commitments, not just traditional extracurriculars.

Depth matters more than breadth. Stanford directly states that depth in one or two activities can matter more than a long checklist, an approach perfectly suited to students with focused academic pursuits.

MIT explains it asks for your key activities because "academics don't shape your whole personal context." Johns Hopkins describes its "Impact & Initiative" lens as examining roles and impact in clubs, jobs, internships, or within family and community. Notice what's missing? Any requirement that those activities be athletic.

The Data: Most Admitted Students Aren't Varsity Athletes

Even at universities with prominent athletics programs, varsity athletes represent a minority of the student body:

Princeton: ~20% of undergraduates play varsity sports

MIT: ~25% participate in varsity athletics

Stanford: ~12% are varsity student-athletes

Think about what this means: at these supposedly "athletics-forward" institutions, 75-88% of students are not varsity athletes. The majority of admitted students got in without playing college sports, and many without playing high school sports either.

So Why Do People Think Sports Are Required?

The confusion stems from conflating several distinct things:

1. Recruited athletes have an admissions advantage (true)

If you're being recruited to play a varsity sport in college, that's a specific pathway with its own process. But that's completely separate from the question of whether non-recruited applicants need sports on their résumé.

2. Extracurricular engagement matters (true)

Common Data Set reports consistently show that top universities rate "extracurricular activities" as "Important" or "Very Important." But here's the critical point: in CDS definitions, "extracurricular activities" explicitly includes athletics among many other categories, clubs, student government, performing arts, research, work, family responsibilities. Sports is one optional instance of a broader category.

3. Sports correlate with other advantages (true, but problematic)

Recent research analyzing nearly 6 million college applications found that sports participation correlates strongly with socioeconomic status. Private school students reported about 35.8% more sports activities than public school students. This isn't because sports make you more qualified, it's because sports often require resources (equipment, travel, fees, time) that not all families can provide.

If colleges treated sports as a de facto requirement, they'd be creating an inequitable barrier. And increasingly, admissions offices are aware of this.

What If You're "All-In" on Academics?

Here's where nuance matters. Let's distinguish two scenarios:

Scenario 1: Deep Academic Engagement Beyond the Classroom

If your "all-in academics" includes:

Independent research or projects

Academic competitions (math olympiad, science bowl, debate, etc.)

Building tools, apps, or technical projects

Tutoring or teaching others

Writing, blogging, or creating content about your interests

Academic clubs with meaningful involvement

You're fine. This is substantial engagement outside of coursework. You're demonstrating initiative, depth, collaboration, and intellectual community, exactly what admissions offices say they're looking for.

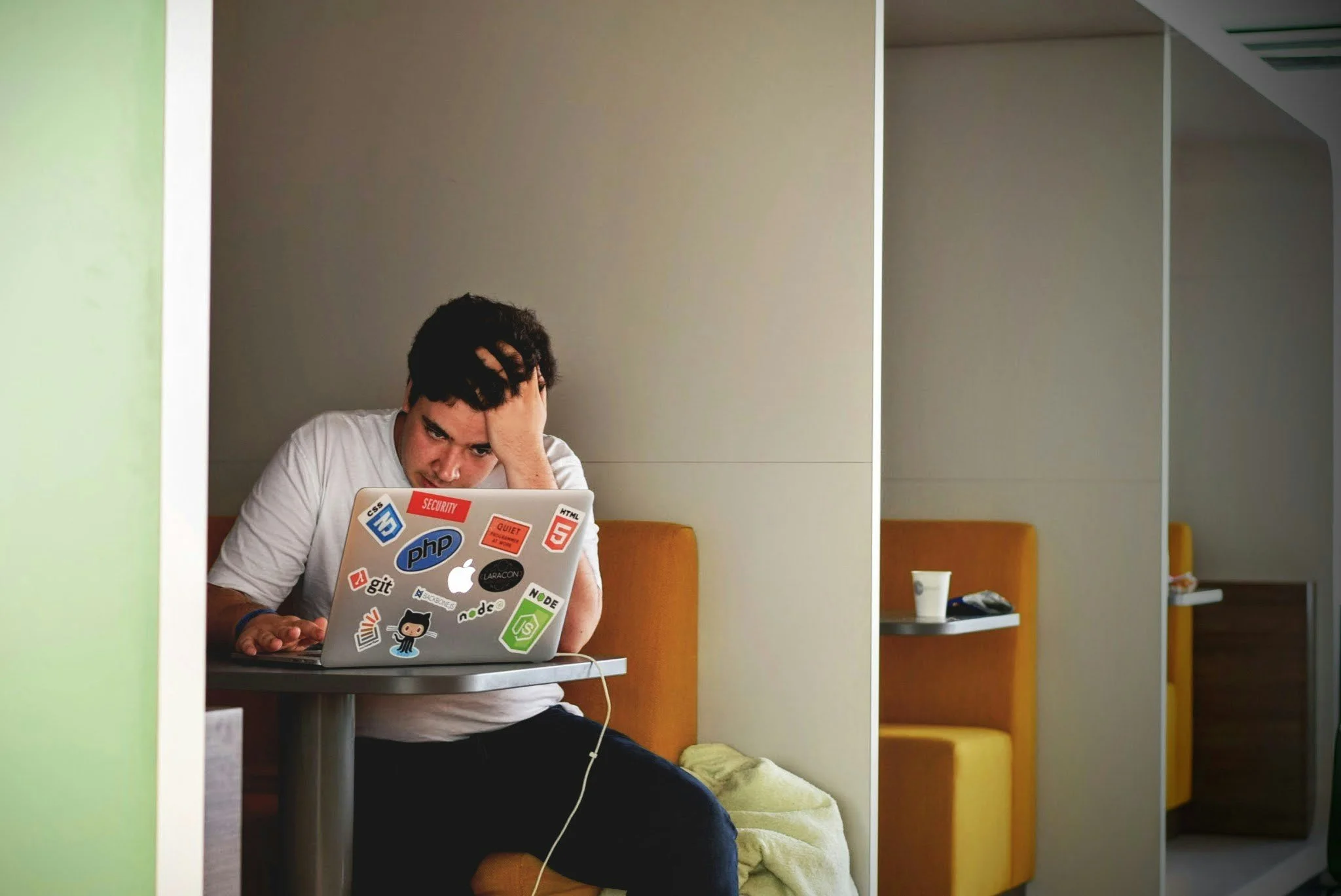

Scenario 2: Only Coursework and Test Prep

If your activities list is literally empty because you focus exclusively on grades and standardized tests, that's potentially a weakness, but not because you're missing sports specifically.

The concern is that you're not showing what Princeton calls evidence of "leadership, initiative, collaboration, or service." You're not giving admissions officers a window into who you are beyond your transcript.

That said, context matters enormously. If you're working 20-30 hours per week to support your family, or providing caretaking for siblings or relatives, or dealing with significant personal challenges, those are meaningful commitments that explain limited extracurricular involvement. Cornell and Princeton explicitly recognize work and family responsibilities as valid "activities."

Bottom Line: What Should You Do?

If you don't play sports and have no interest in starting just to fill a line on your activities list: Don't.

Admissions officers are remarkably good at spotting résumé padding and activities done purely for college applications. Yale's warning about not worrying "too much about any one" component is as much about authenticity as strategy.

Instead:

1. Go deep in what you care about. One or two activities where you've made genuine impact will always beat a scattered list of superficial involvements.

2. Show engagement beyond coursework. Even for the most academically-focused students, this might mean research, competitions, teaching others, building something, or contributing to an intellectual community online or at school.

3. Communicate context. If work or family responsibilities limit your activities, make sure that's clear in your application. It's not a weakness, it's important information about your circumstances.

4. Don't manufacture a sports narrative if it's not authentic. Three seasons of JV cross country where you were an unenthusiastic back-of-the-pack runner doesn't strengthen your application just by existing.

The Real Risk Isn't "No Sports"

The real admissions risk is: no signal of engagement beyond academic requirements.

Sports can provide that signal. So can research. So can coding projects, tutoring, writing, art, music, robotics, environmental advocacy, starting a small business, or any number of other pursuits.

Top universities want to understand who you are and what you'll contribute to their campus community. They want to see initiative, depth, and impact. They want students who are genuinely curious and engaged with the world beyond their transcript.

You can demonstrate all of that without ever setting foot on an athletic field.

If you need help trimming the fat of your current extracurriculars so you can use your time better to distinguish yourself, need help selecting which activities to participate in, or have any other questions related to the college admissions process, schedule a free consultation with an admissions expert today.